“So then the Lord Jesus, after he had spoken to them, was taken up into heaven, and sat down at the right hand of God.” (Mk 16:19).

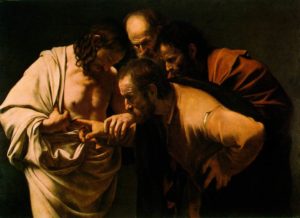

OK. Am I stating the obvious, by saying the disciples’ jaws must have felt sore from dropping each time they saw Jesus after his resurrection? That seems a safe bet, particularly in the days shortly afterward. No one comes back from a Roman crucifixion, especially one that used nails (instead of only rope), thorns and a lance.

And how about that stone tomb, and the massive wheel used to seal it? It’s no wonder the Apostles did not believe Mary Magdalen’s report (those “Doubting Apostles“–not just Thomas!). I can imagine multiple private conversations among those men, and all of Jesus’s followers, each seeking reciprocal reassurances of sanity. But I think it reasonable to conclude that spending 40 days with the Christ in their “Apostolic training program” would decrease the jaw-dropping–just a little.

Nothing is accidental when it involves the Son of God, as you can probably imagine by his use of a 40-day period to prepare his most intimate followers to go forth and “make disciples of all nations…” (Mt 28:19). After all, he completed his own 40-day program (in the wilderness) prior to beginning his public ministry. And as a faithful Jew, he knew of the Israelites 40 years in the wilderness

Some of you may have noticed an interesting similarity, and contrast, involving the wording used to describe Christ’s Resurrection (an Ascension in its own right) and his Ascension. In I Corinthians 15:20 Christ “has indeed been raised from the dead;” and the Eastern Church uses “Analepssis” or “the taking up” for Christ’s ascension. Both seem to imply that Christ either didn’t or couldn’t raise himself–either from the dead or into heaven; but then in the Creeds of both the Apostles’ and the Nicene Council Christ “rose from the dead,” thereby indicating an act of his own power. And then we turn our attention to the Latin Feast of Ascensio, which seems to straddle both meanings: “Christ was raised up by his own powers.”

Finally, who was it that died on the Cross? The explanation needed to help us understand all this is found in the two natures of Jesus the Christ. The human nature of Jesus of Nazareth died on the Cross, was raised from the dead and was assumed into heaven; but the divine nature of Jesus the Christ, the God as 2nd person of the Trinity, never died on the Cross but surely rose from the dead and ascended into heaven–of his own power!

Now that I’ve settled that controversy, with a Council of…One!

In John 6:62, Christ asks the Jews:

“Then what if you see the Son of Man ascend up where He was before?”

This refers to the heavenly person in Daniel 7:13:

“In my vision in the night I continued to watch, and I saw One like a Son of Man coming with the clouds of heaven. He approached the Ancient of Days and was led into His presence. And He was given dominion, glory, and kingship, so that every people, nation, and language should serve Him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that will not pass away, and His kingdom is one that will never be destroyed.”

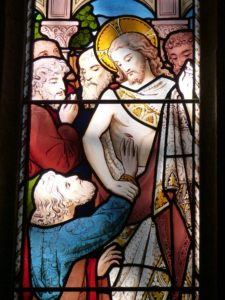

Jesus gently admonishes Mary Magdalene to not attempt to hold him, which she desires because she wants to keep Jesus with her; but he must first ascend to heaven and to his Father, so that he can return to his disciples in spiritual and sacramental ways:

“Do not touch Me, for I am not yet ascended to My Father, but go to My brethren, and say to them: I ascend to My Father and to your Father, to My God and to your God.” (Jn 20:17) Mary

St Paul tells us in his letter to the Ephesians,

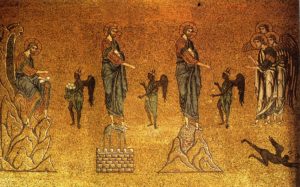

“Therefore it is said, ‘When he ascended on high he led a host of captives, and he gave gifts to men.’” (Eph 4:8-10)

And he shares a similar theme in his first letter to Timothy, saying:

“He was…taken up in glory.” (I Tim 3:16)

Does Jesus abandon the Apostles and Disciples? Pope Benedict tells us that the Apostles have a new understanding of Jesus, and believe in a new presence of him—one powerful and deeply personal. He is not “up in the cosmos,” but rather close to them (That makes me think, “wherever 2 or 3 are gathered in my name”) so that they experience lasting joy—not sadness! Remember their 40 days of training…

Benedict teaches us that the cloud that helps Jesus ascend has great theological meaning:

- Cloud at Christ’s Transfiguration

- “Overshadowing” to Mary, of the power of the Most High

- “Holy Tent” of God in the Old Covenant, where the Cloud represents God and is the same Cloud that led the Israelites out of the desert.

Sitting at God’s right hand means sharing in the dominion over space and all creation. So this exalted position makes clear that Jesus is not the son of David, but rather David’s Lord. And since Jesus is with the Father, he is closer to us than ever. So his “going away,” in John, will actually bring him closer to us, because he will be in communion with the Father. That’s a paradox, but a blessing as well.

And it helps us understand Jesus with great joy, when he tells the Apostles (and us):

“I go away, and I will come to you.”

His Ascension moves him away from one place at one time and throughout history and in every place, sending the Holy Spirit, the Counselor, the Paraclete to all who believe–including those 11 men (and Mary) praying in an Upper Room in Jerusalem–and thus the Church begins…

As part of their preparation for receiving the “promise of the Father” (i.e., the power of the Holy Spirit, Acts 1:4-5), Christ instructed the Apostles to stay together and pray together. These instructions called to mind the exhortation and warning attributed to Benjamin Franklin to his fellow Founding Fathers, at the signing of the Declaration of Independence: “Gentlemen, we must, indeed, all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.” The similarities don’t end there, considering the small band of patriots seeking to begin a new nation, while opposed by the English military, the greatest power in the world at that time. I could go on…

By instructing his disciples to remain together, in prayer, he insured that they could build–and model for future generations how to build–Christian communities throughout the world. As Pope Benedict tells us in his 2006 homily on the Solemnity of Pentecost, “To stay together was the condition laid down by Jesus in order to receive the gift of the Holy Spirit; the premise of their harmony was prolonged prayer. In this way we are offered a formidable lesson for every Christian community” (emphasis added). I printed those two words in bold type in order to emphasize the importance of a shared faith built upon relationships based upon God’s love.

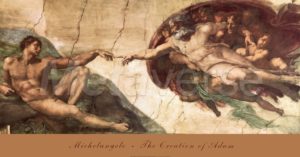

And what is the ultimate example of a loving relationship and loving community? The Holy Trinity.

In many forums I’ve emphasized this community aspect, after learning how crucial it was to sustaining the early Church and to growing it. Persecution was rampant during that time (and at other times, including–increasingly–our own), and a solo faith would have wilted under the withering assault of the state and other hostile groups. We need encouragement from fellow believers, as one’s strong faith can help another’s weakened belief. The Apostles learned that the glue that could keep them together while they waited for the fulfillment of God’s promise and ever after, was prayer–as a community!

For years I preferred a private, personal faith, on my own terms; and one way that manifested itself was my withdrawal from the “Handshake of Peace” during Mass. I’m sorry I did that, and modeled that for my children. I had no understanding of, let alone appreciation for, the community of believers and all its blessings. But I learned to open myself to the camaraderie waiting for me, as have they, despite the “risk” of catching germs from the person who coughed in his hand or having the brief embarrassment of facing the person I cut off in the parking lot. I still find it amazing when women whip out from their purses the hand sanitizer bottles (to be shared by their husbands, I might add), unaware that the only way that lotion might work is if the entirety of both hands were vigorously rubbed together for at least 30 seconds including under the tips of the nails (an action I’ve never seen!) And in my nearly 63 years, I’ve yet to see this reaction to a handshake outside of church. O “we” of little faith!

I’ve described the importance of “community” in a variety of forums, including previous blog posts, during presentations and on a radio show I co-host with my brother in Christ and beloved friend Dan Duddy (“The 13th Apostle,” Saturdays @ 11:30 am on WQPH radio 89.3 FM in the Shirley/Fitchburg MA area, or streaming on WQPHradio.org and archived at this link)

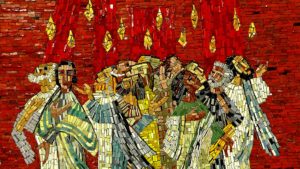

As is so often the case in our Sacred Scripture, the New Testament helps unfold and develop a truth of the Old Testament. Pope Benedict tells us that God initiated his covenant to the Israelites in Sinai (Ex 19:3) with his first revelation of himself to them. This “Feast of Sinai” was celebrated 50 days after Passover, as Feast of the Covenant–with only the people of Israel. The “tongues of fire” described by Luke (Acts 2:3) in Christ’s Pentecost echoes that, but describes a different seminal event: the Feast of the New Covenant (“Behold, I make all things new”), one between God and all mankind through the actions of Jesus Christ and the intercession of the Holy Spirit!

The arrival of the Holy Spirit in the Upper Room must have resulted in stunned amazement, great joy and perhaps more jaw-dropping! However some in the vicinity, upon hearing the enthusiasm and multiple tongues, mocked the Apostles by saying their testimony was fueled by drunkenness (Acts 2:13). This is a weak accusation, considering the early time of day (“third hour” is 9:00 am) and that Jewish followers of the Christ fasted during the morning of Pentecost.

Peter stood with his brothers in faith (remember: Community), lifted up his voice while recalling their ancient prophet:

“And in the last days it shall be, God declares, that I will put out my Spirit upon all flesh…And it shall be that whoever calls on the name of the Lord, shall be saved.”

Note the “whoever.” Peter testifies to the New Covenant assurance noted above, that salvation belongs to all mankind who believe in Jesus Christ–not just the Jews rescued from Jerusalem (after the destruction of the Temple by the Romans), not just men and not just free.

The most important point to make about Christ’s Ascension and the Holy Spirit’s Pentecostal descent, is that these actions–not just states of being, but actions–demonstrate their limitless love for us. The most important aspect of God is not that he is love, but that he does love–because had he not loved us, we wouldn’t know about that love or about him.

Now it’s our turn: let us “go forth and make disciples of all nations,” doing so in the name of the loving Father, and of the loving Son and of the loving Holy Spirit!”

Amen.

Tom

During my adulthood, the faithful could hear an additional message from priest, deacon or minister: “Repent, and return to the Gospel.” While I like both exhortations to get one’s life back in proper order, the newer version gives a more direct message: we need to repent of our sins, and live as Jesus lived. We need to seek forgiveness, do penance and become reconciled with our Heavenly Father. The older message may be fine for an older population, as we (it used to be “they,” until I passed age 60!) can understand the implication of both the ashes and the message: you are much closer to ashes than to youth, so turn your life around before it’s too late! But by far the most important part of the Lenten message is, and should be, one of Joy, as indicated by the prayer said before the Masses of the season:

During my adulthood, the faithful could hear an additional message from priest, deacon or minister: “Repent, and return to the Gospel.” While I like both exhortations to get one’s life back in proper order, the newer version gives a more direct message: we need to repent of our sins, and live as Jesus lived. We need to seek forgiveness, do penance and become reconciled with our Heavenly Father. The older message may be fine for an older population, as we (it used to be “they,” until I passed age 60!) can understand the implication of both the ashes and the message: you are much closer to ashes than to youth, so turn your life around before it’s too late! But by far the most important part of the Lenten message is, and should be, one of Joy, as indicated by the prayer said before the Masses of the season: